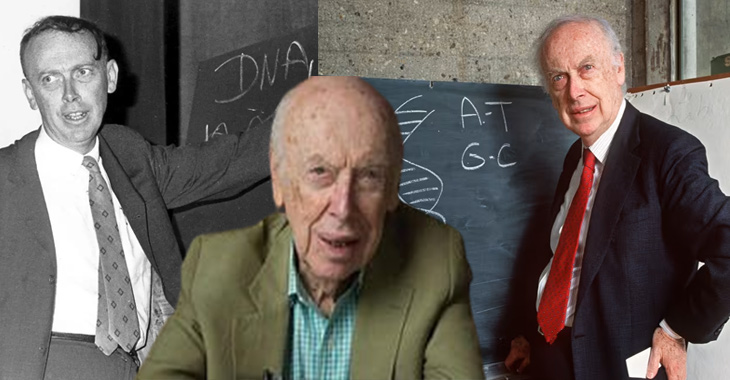

James D. Watson has passed away at 97. His co-discovery of DNA’s twisted ladder structure in 1953 ignited a long-lasting revolution in ethics, genealogy, medicine, and criminal prevention.

He was born in Chicago on April 6, 1928, the son of a mail-order school bill collector who had authored a little book about birds in northern Illinois. At first, the younger Watson wanted to pursue his father’s hobby of studying birds. He once remarked, “My greatest ambition had been to find out why birds migrate.” “The career would have been lost. They are still in the dark.

The intelligent child who enjoyed reading the World Almanac made an appearance on the well-known radio program “Quiz Kids” when he was 12. His adolescent years were difficult, as is frequently the case for bright people. Watson remarked, “I never even tried to be an adolescent.” “I never attended gatherings for teenagers. I was out of place. I had no desire to blend in. I essentially transitioned from childhood to adulthood.

At the age of 15, he was accepted into a program at the University of Chicago that aims to offer gifted children an early advantage in life. He acquired the Socratic technique of inquiry through oral confrontation there, which would serve as the foundation for both his outstanding accomplishments and the severe verdicts that would ultimately lead to his downfall.

It took Watson decades to feel deserving of a breakthrough that some compare to Einstein’s well-known E=MC2 formula. However, he succeeded. “Did Francis and I merit the double helix?” Forty years later, Watson posed a hypothetical question. “Yes, we did.”

The bold, Chicago-born Watson became a revered figure in science for decades after the discovery, which was made at the age of just 24. However, when his life was coming to an end, he was subject to professional criticism and condemnation for making inappropriate statements, such as claiming that Black people are less bright than white people.

For finding that deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, is a double helix made up of two strands that coil around one another to form what looks like a long, gently twisting ladder, Watson received the 1962 Nobel Prize with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins.

That insight was revolutionary. It immediately implied how DNA is duplicated during cell division and how genetic information is stored. The two DNA strands pull apart like a zipper to start the duplication.

The double helix would become an easily identifiable symbol of science even among non-scientists, appearing in places like Salvador Dali’s artwork and a British postage stamp.

More modern advancements like manipulating the genetic composition of living organisms, curing illness by introducing genes into patients, identifying human remains and criminal suspects from DNA samples, and tracking family trees and ancient human ancestors were made possible by this discovery. However, it has also brought up a number of ethical issues, including as whether we should change the body’s blueprint for aesthetic purposes or in a way that affects a person’s progeny.

Watson once remarked, “It was pretty obvious that Francis Crick and I made the discovery of the century.” “We could not have predicted the explosive impact of the double helix on science and society,” he wrote later.

Watson never produced another significant discovery in the lab. However, in the decades that followed, he contributed to the direction of the human genome mapping effort and produced a best-selling biography and influential textbooks. He selected and assisted promising young scientists. Additionally, he influenced scientific policy through his connections and prominence.

Duncan Watson described his father as someone who “never stopped fighting for people who were suffering from disease.”

Watson’s initial motivation for sponsoring the gene project was personal: Watson reasoned that understanding the full composition of DNA would be essential for comprehending schizophrenia, possibly in time to assist his son Rufus, who had been admitted to the hospital with a potential diagnosis.

In his best-selling 1968 book about the discovery of DNA, “The Double Helix,” he remarked, “a goodly number of scientists are not only narrow-minded and dull, but also just stupid.”

He wrote: “You have to avoid foolish people if you want to succeed in science. Never engage in activities that bore you. Leave research if you are unable to coexist with your true peers, even your scientific rivals. A scientist must be ready to get into serious difficulties in order to achieve great achievement.